After years of setbacks, dementia researchers are getting excited about a new antibody drug called lecanemab. No one expects it to stop cognitive decline, but even slowing it would be a breakthrough

This year’s meeting is poised to be a landmark event. After more than a century of research into Alzheimer’s, scientists expect to hear details of the first treatment that can unambiguously alter the course of the disease. Until now, nothing has reversed, halted or even slowed the grim deterioration of patients’ brains. Given that dementia and Alzheimer’s are the No 1 killer in the UK, and the seventh largest killer worldwide, there is talk of a historic moment.

The optimism comes from a press statement released in September from Eisai, a Japanese pharmaceutical firm, and Biogen, a US biotech. It gave top-line results from a major clinical trial of an antibody treatment, lecanemab, given to nearly 2,000 people with early Alzheimer’s disease. The therapy slowed cognitive decline, the statement said, raising hopes that a drug might finally apply the brakes to Alzheimer’s and provide “a clinically meaningful impact on cognition and function”.

The announcement was greeted, broadly, with delight and relief from researchers who have endured failure after failure in the long search for Alzheimer’s drugs. But even the most enthusiastic conceded that significant questions remained. With only a press release to go on, it was hard to be sure the claims stood up. The answer will come on 29 November when researchers leading the trial, named Clarity AD, present their results at the San Francisco meeting.

Lecanemab has already sparked debate. Antibody drugs are so costly they are beyond the means of many countries. Lecanemab itself is not easy to administer, unlike pills and capsules: patients are required to attend clinic for an intravenous infusion twice a month. And the side-effects call for extensive monitoring: patients on the trial had regular scans for brain swelling and haemorrhages, a service many hospitals cannot provide at scale.

More importantly, lecanemab might not work very well. From the data released so far, it is unclear what difference it could make to the devastating burden inflicted by Alzheimer’s. Some doctors warn that the benefits of the drug seem so small, patients may not even notice. But others counter that any effect on Alzheimer’s deserves celebration: it proves the disease can be beaten, or at least slowed down. It’s a start, a concrete foundation to build on.

“Dementia is a global economic disaster as people are institutionalised while their disease progresses at huge cost to society and healthcare systems,” says Prof Giovanna Mallucci, former centre director of the UK Dementia Research Institute at the University of Cambridge, now principal investigator at Altos Labs. “If you can slow the decline, even a small amount, you will really start to see an impact at the economic and medical level.”

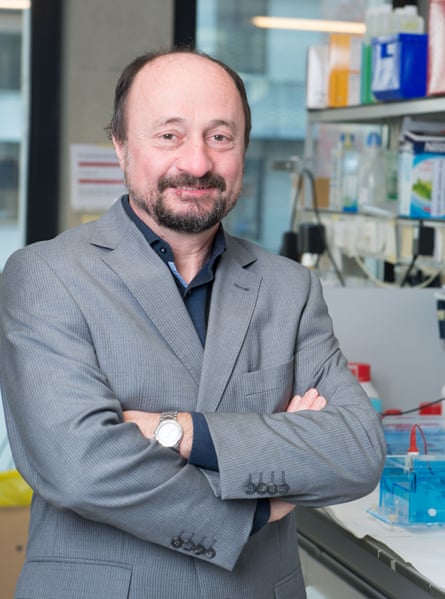

Researchers liken the situation to the HIV crisis in the 1980s. The first anti-HIV drug was far from ideal, but it paved the way for the highly effective therapies used today. “When you have that first breakthrough, it’s like the hole in the dyke that leads to a bigger hole,” says Prof Bart De Strooper, director of the UK Dementia Research Institute at University College London. “There is much more belief now that we can find something. As a doctor, I feel like we might be able to offer something decent to patients within the next few years.”

“This is not a cure by any stretch of the imagination, but if it does slow cognitive decline, it means that for the first time we are modifying the disease,” says Dr Richard Oakley, head of research at the Alzheimer’s Society. “We need to understand the real-world clinical benefit, but I’ve spoken to people and where there’s never been excitement, always hesitation, this does look like the real deal. We need to see the data, but everyone is now saying this is the beginning of disease-modifying treatments.”

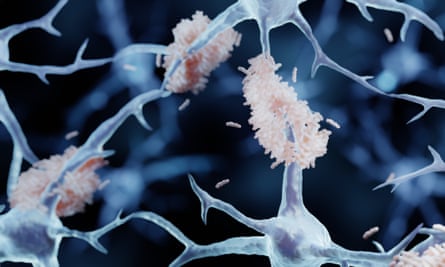

The cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s arises from the relentless destruction of neurons, the cells that ferry information around the brain. The effect goes far beyond normal age-related brain shrinkage: on death, a patient’s brain can weigh 140g less than before the disease took hold – a reduction of more than 10%.

Exactly what kills the brain cells is still up for debate. In some families blighted by early onset Alzheimer’s, scientists have found mutations that cause abnormal clumps, or plaques, of a brain protein called amyloid beta to build up between neurons. Above a certain tipping point, these plaques seem to aid the formation of harmful tangles of another brain protein called tau. These accumulate inside the neurons themselves. More tangles tend to mean greater cognitive decline.

But inherited forms of Alzheimer’s are rare. In most patients, the decline is likely to be driven by a messy mix of processes, which fuel one another. Amyloid and tau are still in the frame, but other toxic proteins, chronic inflammation, vascular problems, cellular health, and faulty disposal of waste from the brain may all contribute. “If we think about Alzheimer’s in old age, I don’t think most of these people have pure Alzheimer’s,” says De Strooper. “I think they have mixed forms of dementia. It’s not always clear what’s really driving the disease.”

Efforts to develop Alzheimer’s drugs have focused overwhelmingly on amyloid. Some aim to block enzymes involved in the production of abnormal amyloid, while others, such as lecanemab, are antibodies designed to clear it from the brain. Between 2007 and 2019, more than a dozen final-stage, or “phase 3”, trials of amyloid-targeting drugs reported results. None slowed cognitive decline; some even made it worse.

The failures split the research community. Some threw out the entire amyloid hypothesis. Others concluded that even if it was valid, amyloid wasn’t the best protein to target. Further concerns surrounded the trials themselves: many enrolled patients who already had Alzheimer’s symptoms. For them, removing amyloid may be too little, too late: snuffing out the match once the fire is raging. The problem is compounded by the insidious early phase of the disease, which destroys neurons without people noticing. “Your brain is so plastic that it can cope with a lot of damage before it starts to show symptoms,” says De Strooper.

But the FDA granted “accelerated approval” because it cleared amyloid plaques from patient’s brains, and therefore might slow the progression of Alzheimer’s if taken early enough, and for long enough. Several scientists resigned from the committee in protest, including Prof Aaron Kesselheim at Harvard Medical School, who told the regulator that its ruling was “probably the worst drug approval decision in recent US history”.

The FDA will rule on lecanemab in January 2023, with decisions in the UK and Europe to follow. While press-released data from the lecanemab trial suggests the drug slowed cognitive decline, the effect was small. After 18 months, cognition declined 27% less in those who took the drug compared with those on a placebo. On a common dementia rating scale, which scores people from 0 to 18 on memory, problem-solving and other tasks, those on lecanemab performed only 0.45 points better. The result is statistically significant, but it may not mean much for individual patients.

One idea gaining ground in Alzheimer’s research is that drugs will need to remove amyloid fast to have any hope of showing a clinical benefit. The logic is laid out in a 2022 paper by De Strooper and Eric Karran at AbbVie, a US biopharmaceuticals firm. They argue that it will take time for the effects of amyloid removal to show up in thinking and memory tests. If a drug doesn’t push amyloid low enough, or takes years to do it, it probably won’t help, they suggest, at least not in the timeframe of most clinical trials.

Despite lecanemab’s reportedly small effect, Mallucci sees positives in the results. “What really needs to be trumpeted from this trial [assuming the results hold up] is that you can change the rate of decline of the disease. That half a point is subtle and the individuals might not feel very different, but you can build on it,” she says.

Chronic underfunding means patients have already waited too long for progress. Earlier this year, De Strooper searched the US medical database PubMed for dementia. He found 250,000 studies. He then searched for cancer and found 4.7m. Next, he searched for Covid, a disease that didn’t exist before 2019, and found 300,000 studies. It’s a rough metric, but it suggests that more research has been done on Covid in the past three years than on dementia in the past century.

The comparison with cancer is particularly striking. Decades of substantial funding and research have transformed cancer diagnosis and care. Under NHS England targets, people should wait no more than 28 days from referral to hear whether or not they have cancer. But for dementia, NHS England has only an “ambition” to diagnose two-thirds of patients. No timescale is mentioned.

With cancer, the full suite of diagnostic equipment is brought to bear on patients, from genome sequencing to advanced MRI and PET scanners. People often receive a detailed diagnosis of the cancer they have. Dementia diagnosis and care lag far behind. If Alzheimer’s patients can benefit from amyloid-clearing treatments, they will need an early diagnosis and evidence of amyloid in the brain. UK clinics are not close to being able to offer such services. “We could be in the situation in 2025 when we have access to a drug that modifies disease but are unable to give it to those most likely to benefit because we diagnose them too late and unspecifically,” says Oakley.

The real hope may lie in entirely different approaches. Antibodies may help some Alzheimer’s or pre-Alzheimer’s patients, but to have a major effect on the disease, a combination of drugs that hit different biological processes is needed. “I suspect antibodies will have a place for a small number of carefully selected patients, but we need multiple approaches,” says Mallucci. “This isn’t a feasible way forward for dementia treatment on a global scale. It’s not feasible economically or logistically.”

One idea is to administer vaccines that prompt the patient’s immune system to churn out antibodies to clear problematic amyloid and tau. De Strooper believes drugs that block key enzymes needed for the production of harmful amyloid are worth another look. Mallucci favours drugs that make the ageing brain more resilient, by protecting and reinvigorating brain cells. There are many potential approaches, including boosting the brain’s ability to clear toxic proteins and targeting inflammation. She has pioneered work on increasing the fitness of diseased brain cells, the ability to make new proteins, and on the “cold-shock” protein RBM3, which mammals release in hibernation and hypothermia. Both these approaches help to regenerate synapses, the connections between neurons, and – in mice, at least – help to protect against dementia by boosting memory and preventing brain cell death.

Another line of attack is to boost a compound called BDNF, which might also reinvigorate cells and help them build new connections. A new clinical trial at the University of California, San Diego, is about to test whether a BDNF-boosting gene therapy can help patients with early Alzheimer’s.

And this is what the field needs, says Oakley: more funding, more approaches, more trials. “We are beginning to see a future where we can make dementia a chronic condition, one you live with and die with but don’t die from,” he says. “We’ve seen it work in every other major condition that research has tackled, and we will see it in dementia. This first generation of amyloid-clearing drugs is only the beginning.”