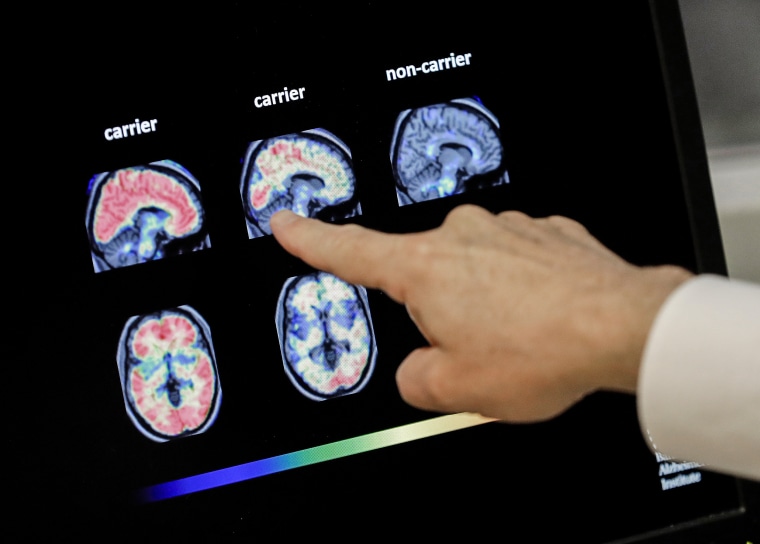

A doctor looks at PET brain scans in Phoenix in 2018.Matt York / AP file

MIAMI — With Latinos 1.5 times more likely than white people to develop Alzheimer's, researchers are uncovering more information about how genetics plays a role in who is more at risk of developing the disease.

University of Miami researchers have teamed up with doctors in Puerto Rico, Peru and Africa, looking for novel genetic factors that contribute to the risk factor and protection against Alzheimer's, with the goal of finding new drug targets.

They have found that in Puerto Rico, people have a higher propensity for Alzheimer's and part of the reason could be a genetic variant they have uncovered.

There are about 6 million people in the United States with Alzheimer’s, and its prevalence is projected to increase to almost 14 million by 2050. It is the most common form of dementia in the elderly and it slowly destroys memory and thinking skills. There is no cure and available treatments are limited in effectiveness.

One of the groups the researchers are looking into is the Puerto Rican population, which makes up the second largest Hispanic group in the continental U.S. While, in the U.S., 10.7% of the population age 65 and older has Alzheimer's, in Puerto Rico the number is 12.5%. In the U.S., it's the fifth-leading cause of death in those over 65 but in Puerto Rico, it ranks fourth in the same age group.

It was more than three decades ago when Alzheimer’s genetic research pioneer Margaret Pericak-Vance was at Duke University that she began trying to involve more diverse populations in research.

At the time, most genetic-based studies of Alzheimer’s were being conducted in non-Hispanic white populations of European ancestry, with communities of Hispanic and African ancestries largely ignored.

"It just wasn’t done,” said Pericak-Vance, the director of the John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. "But even back then, we thought this has to be important.”

Now, she is spearheading the Hussman Institute as it builds a large genetic database to research aspects of Alzheimer’s and genetic variations among Hispanic communities and those of African ancestry.

Their research is helping fill a major gap in minority research and could play a significant role with Alzheimer’s drug development.

“A genetic target, which drug companies are showing interest in, is twice as likely to be successful therapeutically than nongenetic targets,” Pericak-Vance said.

The Hussman Institute is one of the top programs funded by the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health in the U.S. Since July, they’ve been awarded more than $100 million for research in this area.

A variant of the APOE gene, the APOE4, is considered the most significant genetic risk factor for late onset Alzheimer’s, and most of the studies initially only included people with European ancestry.

“As we started to look at different groups, we saw that the risk was different,” Pericak-Vance said about findings they published in 2018 based on a study of different groups' genomes and APOE. “For example, among individuals of African descent or with some African ancestry, the risk was lower.”

“This paper that we published allowed people to see that ancestry was important and that we had to include diverse populations in research,” she said.

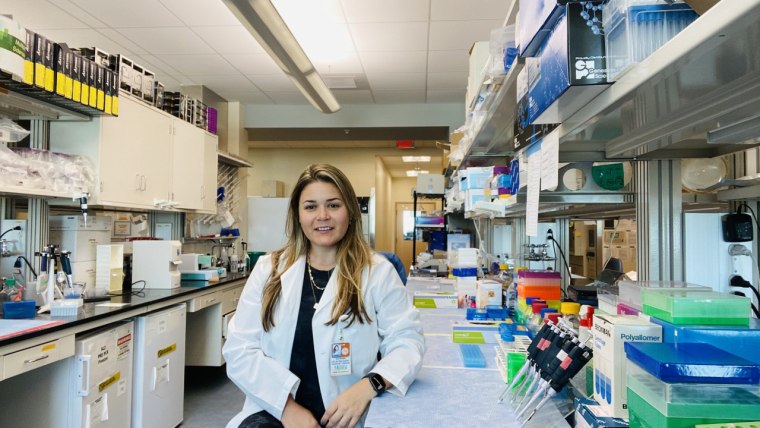

Dr. Katrina Celis, an associate scientist at the Hussman Institute who is studying Alzheimer's in Hispanic populations, has spent the past 13 years focusing on genetic research.

“Coming from an underdeveloped country, I faced and understood the need for inclusion and representation of diverse populations in genetic research,” said Celis, who is originally from Venezuela. “I have mainly focused on increasing genetic research participation from diverse populations, specifically from Hispanic Latino communities.”

Celis is collaborating with Dr. Briseida Feliciano-Astacio, a neurologist and principal investigator from the Universidad Central del Caribe, in Bayamón, Puerto Rico.

Celis and Feliciano-Astacio and the team at the Hussman Institute are studying large families in Puerto Rico and what they call “multiplex families,” which means they have more than two or three individuals who have Alzheimer’s.

Feliciano-Astacio said the island’s aging population is struggling because many younger Puerto Ricans have left due to the economic situation.

"There are many elderly people that are alone," she said, adding that it has affected all socioeconomic backgrounds.

Celis is also focused on a second project studying chromosome 14, which harbors a well-known gene they see in early-onset Alzheimer’s. She said she's trying to identify the molecular mechanisms driving this particular case, and the wide range in age of onset that they see in individuals who carry this particular genetic variant.

A variant only found among Hispanic Caribbeans

Puerto Ricans are a mixed population, and their genetic ancestry is mostly composed of European, African and Native American or Amerindian ancestry.

“We are the first group that identified that this variant actually occurs in African ancestry,” Celis said about the variant on chromosome 14.

“We identified that the particular region that harbors this variant that is associated with Alzheimer’s disease risk lies on the African ancestral background,” said Celis. “However, that particular variant has only been found in Caribbean Hispanic individuals, mainly of Puerto Rican descent, which is known in the genetic world as a founder mutation, meaning something happened in the island after the colonization that created this sort of variant within the genetic information of these individuals.”

Celis and Pericak-Vance agree that including more diverse populations is the only way to move forward.

"Inclusion and awareness are essential to drive precision medicine in diverse populations," Pericak-Vance said.