Clinical trials show encouraging results for a second investigational Alzheimer’s drug — and Brown University, Butler Hospital and Rhode Island Hospital were again deeply involved.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Two important advancements in Alzheimer’s disease research have been made possible by the work of Rhode Island researchers — including Dr. Stephen Salloway, a professor of neurology and psychiatry at Brown University who also directs Neurology and the Memory and Aging Program at Butler Hospital in Providence.

Salloway will celebrate 30 years at Brown this coming summer, and he has been focused on Alzheimer’s disease throughout that entire tenure. Four years ago, he helped lead recruitment and imaging for a clinical trial of a promising Biogen drug called aducanumab, which is currently under U.S. Food and Drug Administration review for approval as a potential therapeutic for Alzheimer’s patients.

This month, Salloway is a co-author of a New England Journal of Medicine study on an Alzheimer’s drug by Eli Lily and Company called donanemab. The study, conducted at 56 research sites across North America, including two in Rhode Island, found that in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease, the use of donanemab resulted in improved cognition and ability to perform routine activities.

Salloway — who is based at Brown’s Warren Alpert Medical School and affiliated with the Carney Institute for Brain Science — shared what the trial results mean, how the drugs are related and Rhode Island’s role in Alzheimer’s research moving forward.

Q: What were the main findings of the trial, and how optimistic do you feel about the results?

This study is a Phase II trial of a new antibody called donanemab, which targets amyloid plaques in the brain and helps to remove them. This treatment is for people with early Alzheimer's disease who have either mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. Fortunately, the drug showed substantial lowering of amyloid plaque and also a slowing down of memory loss on tests of memory and daily functioning. It’s very encouraging to see that the drug may be having the intended effect.

Q: What was unique about this study?

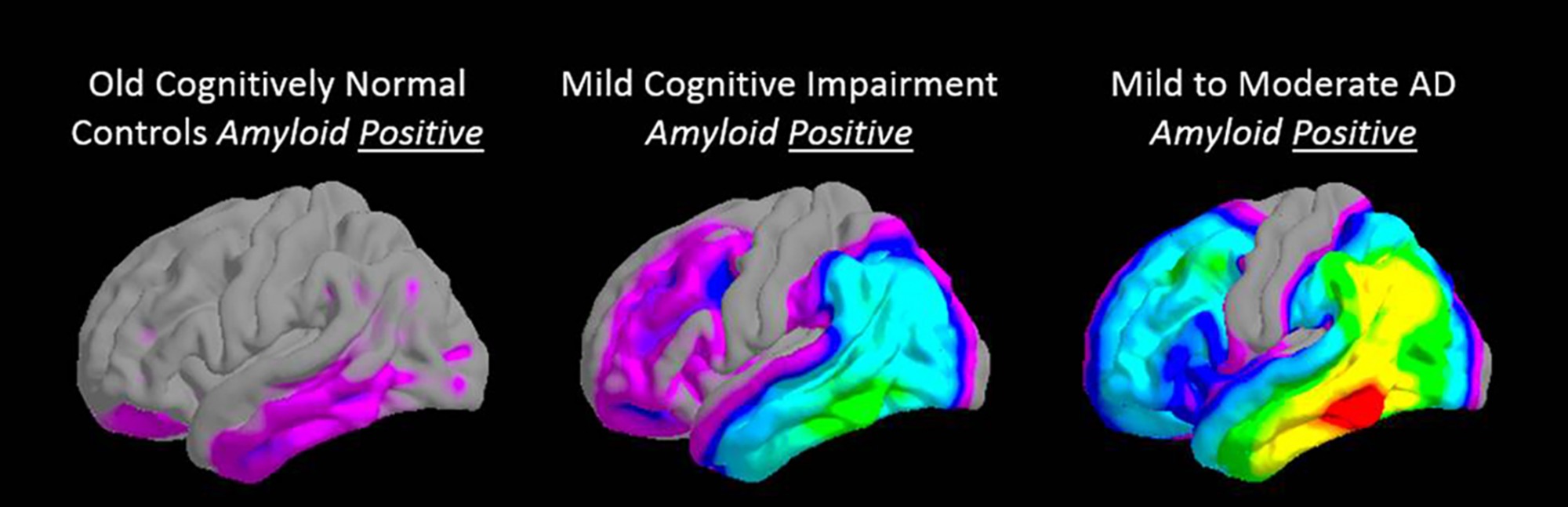

One innovation is that it utilized new imaging technology. Positron emission tomography (PET) tracers, some of which we helped develop at Butler and Rhode Island hospitals, were used for a more precise staging of the disease in terms of the changes in the brain. Trial participants all had to be amyloid positive above a cutoff, and then also had to have, for the first time, a moderate level of tau, which are another marker of the disease. The thinking was that lowering amyloid is better to do in the earlier stages of the disease because that’s when it builds up. And if a patient has advanced levels of tau, they may be less responsive to the treatment.

Something else that was new about this study: Once the PET scan showed that the amyloid levels had been lowered into a more normal range, the treatment was stopped while the patients continued to be monitored. Previously, when we’ve been testing antibodies like this, we continue treatment every month until the end of the study.

Q: What is the difference between this new drug and aducanumab, which you also helped to evaluate?

There are some biochemical differences in that they target different components of the amyloid plaque molecules. But they have the same effect: At low concentrations, they pass the blood-brain barrier into the brain and bind to amyloid plaque. They stimulate the immune system to break up the plaque, and then the plaque is cleared away through the vascular system.

In both studies, we looked at the same disease stage. With aducanumab, only people that were amyloid-positive participated; we didn't use tau as an inclusion criteria as we did in the donanemab study. So participants in the donanemab study may tend to skew a little more toward a milder degree of pathology. In the aducanumab study, there's going to be a bigger range; there may be people with more advanced tau pathology.

The results from the two studies look pretty consistent: Both drugs lowered amyloid and had some benefit in slowing down memory loss. It’s encouraging that this treatment mechanism may have the clinical benefit that's really been our main goal, which is to show that we can target a key component of Alzheimer's disease which is associated with clinical improvement or stabilization.

Q: What are the next steps with donanemab?

Donanemab is currently in a Phase III trial, which will involve a larger number of participants. It’s a pivotal trial to hopefully replicate and expand on the results we saw in Phase II. And if the outcomes are positive, then that drug would be submitted to the FDA for approval.

Q: Aducanumab is currently under FDA review. What do you expect might happen next?

The development process has had its highs and lows, but we'll be hearing in June whether or not aducanumab will be approved. I personally have had 65 people on this drug, some of them for longer than five years. There’s a substantial group that is doing better than expected. I'm hoping that in the future, we’ll be able to more precisely identify who's most likely to respond to the treatment: That’s one of the advances of the donanemab trial, and using tau PET as the marker of tau buildup could be a useful predictor of response for this type of amyloid-targeted treatment. So I'm encouraged by these results from the donanemab study, and I have a good feeling about aducanumab.

If aducanumab is approved, it would be the first disease-modifying type of treatment for Alzheimer’s that targets a core pathology. We hope we will have a new treatment to offer to patients this year. It will open a door in giving us a biological foothold in the fight against Alzheimer's that we can build on and improve upon in our research here at Brown and elsewhere. I’m really excited about that and look forward to the opportunity.