Private equity’s troubled bet on UK nursing homes

By Leah Hodgson

The coronavirus affects all ages but hits the elderly hardest. Those over 70 are the most at risk of developing severe symptoms, and this is painfully apparent in the UK nursing home sector. As of June, almost 19,400 elderly people in care have died from COVID-19, according to government estimates, meaning the virus accounts for 29% of all nursing home deaths. It is the worst crisis the sector has seen, and the numbers are only expected to rise.

The toll from the pandemic has exposed the vulnerability of the sector and its shaky financial condition. Nursing homes in the UK face more than £6.6 billion ( $8.8 billion) in extra costs stemming from COVID-19 and £714 million in lost revenue by the end of September, according to an analysis by the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services, a nonprofit advocacy group.

To see the effects, one need look no further than the plight of the UK’s largest operator, HC-One. In April, the company—currently backed by Formation Capital and Safand—warned that it was struggling to repay debt as falling occupancy and the cost of virus-related protective equipment for staff cut into its income. After uncovering safety lapses in some of its homes, regulators in Scotland called into question HC-One’s license to operate Home Farm, one of its facilities.

Cases such as HC-One’s are showing up across the industry as the pandemic magnifies health and financial problems that surfaced at nursing homes in the aftermath of PE investors swooping in to reshape the industry in recent years.

Over the past decade, PE firms have piled into a sector beset with financial stress brought on by the global financial crisis. Government austerity measures decimated local budgets. Between 2010 and 2018, public spending on adult care fell by £700 million, and the cost of care rose 6.6% from 2015 to last year, according to The King’s Fund, a health-care think tank. Private equity investors were attracted to the industry, sensing potential for high returns in a traditionally stable sector serving an aging population.

"There are fundamental flaws to the business

model of the privatization and operation of care homes."

John Spellar, Labour MP

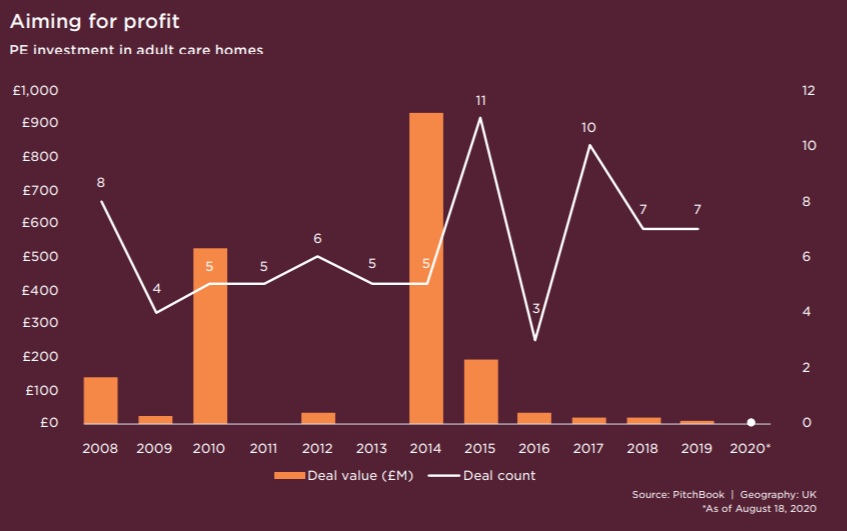

Since 2010, PE firms invested more than £1.7 billion across 64 retirement and nursing homes deals, according to PitchBook data. Today more than 8 in 10 nursing homes in the UK are owned by for-profit operators, according to research by the Institute for Public Policy Research.

But with new capital often comes more debt. Ownership of HC-One changed hands three times in under a decade, each time becoming more indebted. Faced with low levels of local government aid, some PE backers are struggling to service portfolio companies’ growing debt, leading some to skimp on operating budgets to maximize returns. Research from the Institute for Public Policy Research suggests that private operators provide less training and lower pay for staff and have higher staff turnover, contributing to a lower quality of care.

Stress on privately owned nursing homes also has consequences for the public sector. By law, if a large provider fails, local authorities temporarily take on financial responsibility to ensure continuity of care.

“There are fundamental flaws to the business model of the privatization and operation of nursing homes,” said John Spellar, a Labour member of Parliament who has railed for several years against PE involvement in the industry.

"There are only so many patients and earning

potential is limited, so piling on debt can mean

disaster."Sameer Rizvi CEO, RD Capital Partners

“Many nursing homes operate in an environment of profiteering, cost and corner-cutting, all the while their owners are loading them up on debt with high-interest rates and expecting the taxpayer to pay when it fails,” he said. “You can’t tar everyone with the same brush, but a lot are there to make a quick buck and get out before the music stops.”

Dire circumstances

Spellar urged the government to take a deeper look into the sector’s financial condition following the collapse in 2011 of home operator Southern Cross. Under PE ownership, the company turned into a billion-pound business. But after rapid expansion based in part on selling off some properties, Southern Cross was unable to meet rent payments.

In 2019, another large operator, Four Seasons, entered administration after failing to keep up with its heavy debt load. Like HC-One, the company changed owners several times before it was sold to Terra Firma in 2012 for £825 million, including a reported £500 million in debt.

“There are only so many patients and earning potential is limited, so piling on debt can mean disaster,” said Sameer Rizvi, CEO of RD Capital Partners, a healthcare-focused buyout firm that owns several facilities. “Some nursing homes change hands two or three times and it cripples them. It doesn’t work if investors go into the sector looking to exit after five years and they end up doing foolish things to make good returns.”

Rizvi said that the sector faces a slew of bankruptcies mirroring Four Seasons. He added that the way PE investors operate homes is unsustainable because of firms’ shorter holding periods. Pressure from investors looking to exit after five or six years puts pressure on home operators to focus on short-term results and scale back operations at the expense of long-term viability, he said.

But the reality is that the UK’s nursing home sector is in dire need of capital; without a significant amount of public money, it depends on private investors.

Last year, the industry saw two nursing home closures for every opening, according to a study by CSI Market Intelligence. Private equity has become an important source of capital to fund new beds and upgrade assets that the UK increasingly will rely on as the population ages.

Some of the problems stem from light regulatory oversight. After Southern Cross’s collapse, legislation in 2014 mandated that larger nursing home providers, typically privately owned, must disclose financial information to the Care Quality Commission, a UK regulatory body. Although the commission monitors quality standards, it can’t force companies to improve their financial position.

Chris Thomas, senior research fellow at IPPR, said that problems in the sector have been well known for years but, despite much government debate about reform, very little has been done.

“Social care reform historically hasn’t been an area that wins voters over, but with COVID-19 that has started to change,” Thomas said. “The pandemic has really forced a lot of the public to simultaneously come to grips with what social care is and the value that social care workers bring. People will stop tolerating the idea that social care is a kind of political no man’s land. Questions around access, quality and price are growing stronger.”

Thomas argued for a national care regulator to focus solely on the financial health of the industry and establish clear standards, including maintaining cash reserves in case of crisis.

Patient capital

“Without a sustainable funding model, things will continue to deteriorate,” Thomas said. “This by no means, means that private equity shouldn’t be involved, but we need to redress the balance.”

Rizvi said nursing home investors should be required to hold their assets at least 20 years. The idea, which upends the 10-year lifespan of most PE funds, would likely involve an evergreen fund that has no termination date and allows investors to recycle capital from realized returns. Extending holding periods, according to Rivzi, would ease pressure on operators and provide capital to finance acquisitions and invest in technology without relying on more debt.

RD Capital Partners says it has a long-term investment horizon. In 2016, the firm set up a subsidiary that takes stakes in nursing homes with a view to building a larger business. Bridges Fund Management, an impact investor, launched a £50 million evergreen fund in 2016. It has used the vehicle to invest in healthcare companies, including residential and nursing care provider Shaw Healthcare.

“A lot of [nursing homes] are really in need of funding and you can get attractive assets at a bargain price,” Rizvi said. “At the end of the day, we have an aging population and really a captive market. The big mistake to avoid is not overleveraging, because if you don’t have to focus on repaying debt, you can invest more into nursing homes, which means better care for patients and higher returns for investors.”