Trying to understand infections’ persistent effects

ALTHOUGH AMERICANS have survived more than 93 million cases of COVID-19, the disease is not yet fully understood. And for an estimated 10 to 30 percent of those afflicted, the unanswered questions are even more vexing, because their recovery has not been straightforward. For them, the threat of long-term, systemic ill-effects seems increasingly real—and with it, the fear that the acute results of the infection may be accompanied by chronic impacts that pose lasting risks to health and well-being.

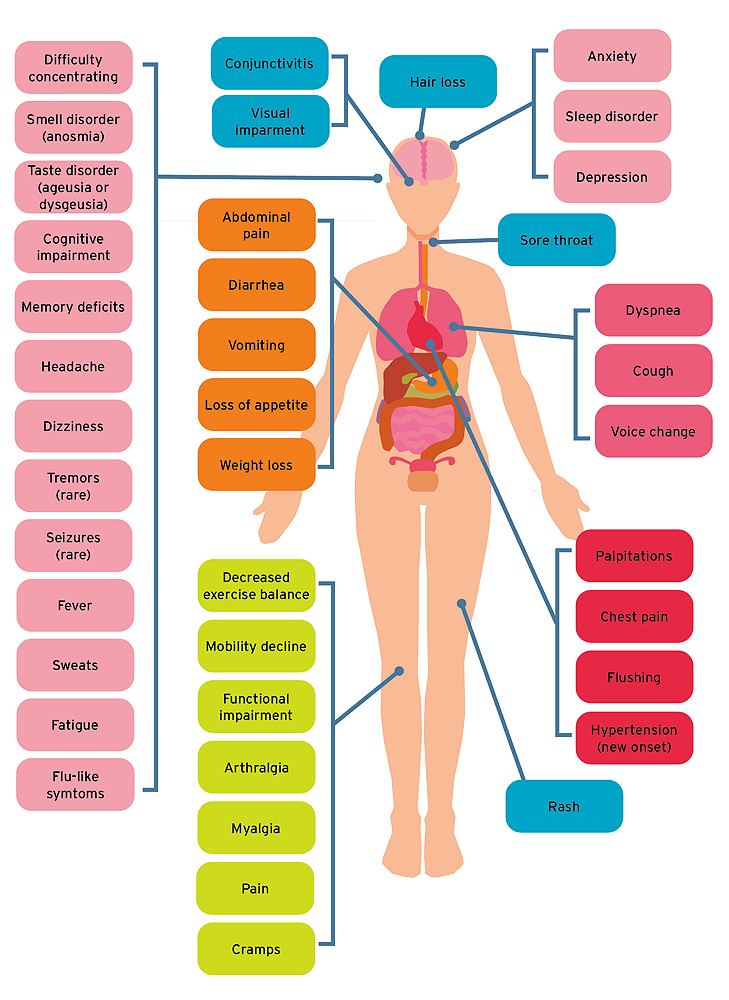

Millions have suffered debilitating symptoms that persist for months, and sometimes years. These lingering after-effects, collectively termed “long COVID,” range wildly, and tend to occur in clusters, centering, for instance, on the cardiovascular system, the lungs, or the gut. Some patients develop irregular or rapid heartbeats, with symptoms developing weeks after they appear to have fully recovered from an initial COVID-19 infection. Others experience joint pain, or nausea, or suffer kidney failure, blood clots, or neurological problems. Most common, affecting more than two-thirds of these long COVID patients, is an extreme, harrowing fatigue, the kind that makes even a small task seem strenuous. That doesn’t mean that an athlete’s six-minute mile becomes an eight-minute mile, says pulmonologist Bruce Levy—it’s much worse than that: “They’re having trouble just walking without their heart racing to 180 beats per minute.”

Living Impaired

PHILIP “PHIL” BACZEWKI knows the anguish of living with these impairments. The 48-year-old father of four—well-known and loved in his hometown of Gardner, Massachusetts, as a social worker, baseball coach, football director, and Boy Scouts leader—was hospitalized with a severe case of COVID-19 in March 2020, as the pandemic began. He recounts the ordeal via Zoom with his wife by his side. “I need her here,” he says apologetically, “because it can be a real struggle to find the words.” Slowly, he recounts how, in the minutes before he was placed on life support, his physician told him to phone his family: his wife, his kids, his Nicaraguan mother. During a coma that lasted 16 days, he was at one point given a 10 percent chance of survival. A priest administered last rites.

“Phil had a very severe case, before vaccines were available,” says Levy, Francis professor of medicine and chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), who began seeing Baczewki in August 2021. “Some of his issues relate to the rigors of intensive care, such as peripheral nerve damage” in his right foot that causes him constant pain. Others, including “changes in blood pressure, decreased exercise tolerance, impairments in functional mobility, gastrointestinal issues, headaches, cognitive impairment, memory deficits, and difficulty concentrating” are common among long COVID patients, says Levy, and are improving slowly.

“When I got home, my blood pressure was through the roof,” recalls Baczewki, “to the point that they thought I would have a heart attack or a stroke.” Now, he can tolerate exercise a few times a week. The day before the Zoom call, he’d ridden a bike for the first time—and fallen. “After 10 minutes, I had to stop because I was exhausted and out of breath. But I did it, you know? I did it.” Speech therapy helped with communication after his hospitalization, but interruptions during a conversation can still overwhelm him.

Such neurocognitive difficulties, including “memory, train of thought and concentration issues, as well as mood disturbances, anxiety, and depression,” seem to last longest among long COVID patients—typically as much as 15 months, says Levy. He also reports an elevated risk of suicide, particularly among those who have lost their senses of taste or smell.

Although Baczewki lost neither sense, grieving the loss of his former self has been traumatic. “I’m not the Phil from March 2020”: not the man who shoveled snow and mowed the lawn for his family; not the social worker who advocated within the court system to protect and place foster children, in simultaneous command of the details of 20 different families; not the coach who taught sports to kids in the community. He tries to “focus on all the blessings I’ve had…to be given another chance…to be here with my family….” But by evening, his diminished connections and abilities, and the frustrations of the day, leave him “filled with rage, ready to lash out. Or [my family] think I’m angry just by the look I’ve given, because I lose tolerance for things.”

Still, Baczewki thinks that in some ways other long COVID survivors have it harder than he does. “They have to prove that they are suffering, that they’re not crazy. When I get that, I can say, ‘Well, I was in a coma. I almost died.’”

The Seeds of a Syndrome

THERE ARE AT LEAST FOUR hypotheses about the causes of long COVID, ranging from inflammation, to a virus-triggered autoimmunity that leads the body to attack itself to—most intriguingly—persistence of viral reservoirs in the body. Their diverse nature, like the breadth of long COVID symptoms themselves, suggests the challenge that confronts scientists trying to come to terms with the syndrome and, ultimately, develop treatments.

• Dormant viruses. A COVID-19 infection could rouse dormant viruses—the way chickenpox can return as shingles later in a person’s life. COVID-19 infection may reawaken dormant reservoirs of Epstein-Barr virus and Cytomegalovirus, both very common causes of mononucleosis, which causes extreme fatigue similar to that observed in long COVID.

• Persistent inflammation. Another explanation focuses on persistent inflammation. Immune responses are beneficial as long as they shut down after an infection has been controlled. When they persist, a host of health problems can ensue. “There are fundamental mechanisms in our bodies to shut immune responses off,” says Levy. “If they don’t work well, the initial surge of inflammation will continue. Certain underlying comorbidities in which these stop signals don’t work well,” such as type 2 diabetes and obesity, “seem to make this long COVID risk higher, but other chronic inflammatory conditions can do it as well.”

• Autoimmunity. Levy cites a study that followed patients in the Pacific Northwest for several months after their initial infection to discover what preexisting conditions raised their risk of long COVID. Among the indicators detected were specific types of autoantibodies, generated when a person’s immune system mistakenly attacks their own healthy cells. None of the patients had ever been diagnosed with autoimmune dysfunction, so “the thinking is that there may be a group of people in which the development of autoimmunity is triggered by the virus,” he says. Irregular heart rate, breathing, and other functions disrupted in long COVID patients, may be related to autoimmune problems. A great deal of scientific work is now focused on trying to establish whether this is true.

• Persistent viral infection. Perhaps the most interesting and concerning theory, Levy says, is that long COVID is caused by virus that persists in the body long after the acute phase of COVID-19 infection ends. Autopsies of COVID-19 patients who died as long as seven months after their initial infection provided the first solid evidence for this idea: virus was found in their lung, heart, brain, gut, and other tissues. Two other studies have detected such viral persistence in the gastrointestinal tract.

Long COVID Symptoms

COVID long haulers report a broad range of symptoms, including fatigue, headache, attention disorders, memory loss, shortness of breath, digestive disorders, and anxiety and depression.

Most recently, Wyss professor of biologically inspired engineering and BWH professor of pathology David Walt and colleagues detected the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein circulating at low levels in the blood of long COVID patients. Walt “created a very sensitive assay for detecting virus in plasma,” says Levy. The results have not been peer-reviewed as of this writing, but they appear compelling. With support from the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness, Walt and colleagues, including professor of medicine Galit Alter, found virus in most of the long COVID patients, but in none of those fully recovered from an initial infection. They hypothesize the existence of reservoirs of the virus in patients’ bodies, where it replicates beyond the reach of the immune system—something Walt demonstrated previously in children with post-COVID multi-inflammatory syndrome (see “The State of the Pandemic,” September-October 2021, p. 36). In these children, virus survived and leaked from the gut into the bloodstream.

If these findings prove accurate, says Levy, and scientists could figure out where and how the viral reservoirs remain embedded in the body, that would be of great medical interest, because it would enable doctors “to use antiviral agents to therapeutically clear the virus, and hopefully, the symptoms along with it. It might help explain why we see such diversity in presenting symptoms, depending on where the virus has found safe harbor in the body.”

Associate professor of medicine Ingrid Bassett, an MGH infectious-disease research physician, agrees that “the idea that people have ongoing viral replication—it could be in the blood, it could be in the gut, it could be in a compartment we haven’t yet interrogated—that might be leading to this ongoing inflammation and immune-system activation” is “a very reasonable hypothesis.” But none of the various explanations are mutually exclusive; all may be true to some extent.

Who Is Most Susceptible?

ALTHOUGH LONG COVID can affect anyone, of any age, the typical patient is middle-aged, generally in her 40s. Some 60 to 70 percent of patients are women. Bassett, who worked with Levy to set up a Boston long COVID collaboration, says there are several possible explanations, all still speculative, for this sex difference. One holds that the syndrome might be caused by autoimmunity. Because women are more likely to suffer autoimmune diseases, this might make them more vulnerable to long COVID, too. But the fact that some studies have found that the excess risk seems to disappear in post-menopausal women, could point to hormones, such as estrogen, as a possible explanatory factor. There are also sex differences, Bassett says, in the density of respiratory tract ACE-2 receptors (which SARS-CoV-2, the virus, uses to infect cells), that might explain women’s heightened susceptibility. But nobody yet knows the reason for the disparity.

Nor is it known whether minority populations are inherently more likely to develop long COVID. Among the adults in the NIH study, “Our target nationally is for 27 percent of participants to be Hispanic or LatinX,” Bassett continues, “and 16 percent to be black or African American”—oversampling relative to the American population for groups of people who were particularly affected by acute SARS-CoV-2 infections. “We’ll try to understand whether identifying as Hispanic or LatinX, or African American, poses an independent risk for developing long COVID,” she explains. If the researchers observe more long COVID cases in that population, they will use statistical techniques “to establish whether the cause is an independent risk factor, or mediated through another variable,” meaning that people who are Hispanic or LatinX may not have an intrinsically higher risk, “but maybe that they live with a higher prevalence of co-occurring conditions, such as asthma,” that elevate risk.

People with more severe infections (minorities have been overrepresented in this category) bear a higher risk of developing long COVID. Among those hospitalized with COVID-19, like Baczewki, more than 30 percent had long COVID six months later, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But even mild or unnoticed initial infections can lead to new, lingering symptoms in some people one to three months later. And people who have been infected more than once during the pandemic run the risk of developing long COVID with each infection. Whether the relative risk of developing long-term symptoms rises with each subsequent infection is not yet known.

Finding and Funding Treatments

EARLY IN THE PANDEMIC, Eckstein professor of economics David Cutler, an expert on healthcare economics, joined with Eliot University Professor Lawrence Summers to estimate that the COVID-19 pandemic would cost the United States $2.6 trillion due in part to the additional economic impact of long COVID. That number, Cutler said in a recent interview, is now closer to $3.6 trillion.

“The relatively meager attention that has been paid to long COVID is unfortunate, because its health and economic consequences are likely to be every bit as substantial as those due to acute illness.”

In a recent article for the Journal of the American Medical Association, he wrote that “the relatively meager attention that has been paid to long COVID is unfortunate, because its health and economic consequences are likely to be every bit as substantial as those due to acute illness.” More than a million people, most of them service workers in fields such as healthcare, social care, and retailing, could be out of the workforce at any given time, he observed, translating to lost income of more than $50 billion annually. Because the shortage of workers in these sectors is already driving up wages and prices, he added in an interview, it could even be contributing to the recent surge in U.S. inflation. Given the immense burden for the economy overall, whatever is spent to understand, treat, and prevent long COVID pales in comparison to the economic costs. “There’s zero argument against spending money—even $50 billion,” said Cutler—“to figure this out.”

Levy and Bassett were the initial organizers of the Greater Boston Recovery Cohort, now one of 15 research groups around the country enrolling patients in a comprehensive $1.15-billion National Institutes of Health (NIH) long COVID study (RECOVER: Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery) that will seek to define the disease, figure out who is vulnerable, discover causes, and develop optimal treatments. As soon as patients began streaming into the COVID Recovery Center Levy had set up at BWH in May 2021, he realized that the wide and puzzling scope of long COVID symptoms would call for an unprecedented level of collaboration among specialists and institutions to understand and treat the heterogeneous syndrome. Six Boston-area academic health centers, including Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston Medical Center, Tufts Medical Center, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Cambridge Health Alliance, ultimately joined forces with the Brigham to form the Boston arm of the NIH-funded research.

“Understanding the underlying biology is key,” says Bassett, “because then we’ll know what approaches to try to treat this.” Now that it is generally agreed that COVID persists for a significant population, the fight against the pathogen and infections has become doubly urgent. The public has an even greater interest in minimizing harm through vaccination and antiviral medications. And there is a pressing need to understand and address the long-term effects many are suffering.

Given the still-obscure causes of long COVID, there are no real treatments—just holistic rehabilitation programs that gradually seek to increase patients’ tolerance for activity. Beyond that kind of palliative care, of the sort that is gradually helping Phil Baczewki, Bassett hopes that treatments will be found, but worries about the perpetuation of inequities. “We need to be sure that as we figure out pathways for managing long COVID—and hopefully treating and preventing it in the future—that we’re really thinking about reaching the broadest possible group of people. Because, I would hate to see a repeat of the gaps in access” to acute COVID prevention, care, and treatment that occur all too frequently in the United States and around the world.