- A new demographic dividend – the “longevity dividend” – is emerging as populations age;

- Singapore, one of the most rapidly ageing populations in the world, and Japan, where around 25% of the population is older than 65, are already responding to this demographic shift and benefit from it;

- From innovative retirement income and care programmes, Japan and Singapore's governments are already seeing positive results.

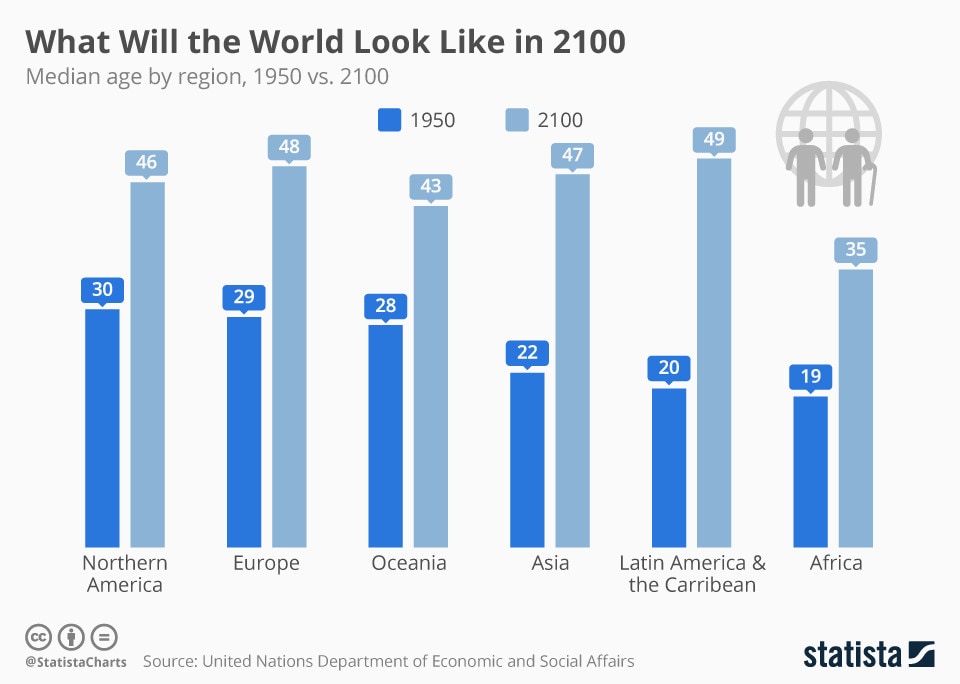

Demographic change has favoured economic growth in many regions around the world. In countries where working-age populations grew more rapidly than the number of consumers, income per capita experienced a boost. This was the first demographic dividend.

However, as is widely acknowledged, this first dividend is transitory because as populations age, the size of the non-working population starts to grow. Even so, the same demographic conditions that are producing an end to the first demographic dividend may yield a second – the “longevity dividend”.

Have you read?

This second demographic dividend is characterized by an accumulation of wealth and savings as older individuals save for consumption at old age and invest in their human capital, especially in health and education. The second demographic dividend can be permanent or self-sustaining as demand for life-cycle wealth stabilizes at a higher level.

All regions in the world can reap the benefits of this longevity dividend. If countries are forward-looking and act early, the opportunities the longevity dividend provides can potentially lead to improved productivity over longer lifespans and an increase in gross national income.

Some countries in Asia, including Singapore and Japan, are responding to demographic shifts and implementing innovative policies and solutions designed to reap the benefits of the longevity dividend.

Singapore: Life-long learning and “risk-pooling”

Singapore is one of the most rapidly ageing societies in the world with a life expectancy of around 83 years. Its government has invested significantly in life-long learning initiatives to boost society’s human capital potential as well as to promote personal development and social integration.

SkillsFuture, a national programme launched in 2014, provides every Singaporean aged 25 and above with an opening credit of $500 that they may use to attend approved skills-based courses. This credit does not expire and the government will provide periodic top-ups. SkillsFuture also offers work-study programmes to strengthen industry-academia interactions for students and mid-career professionals.

Singaporean universities also support their graduates in life-long learning. Alumni of the National University of Singapore can take selected industry-relevant courses for up to 20 years from the time of matriculation; the Singapore University of Social Sciences also offers credits to alumni to offset fees on courses related to emerging skills.

Singapore employs other mechanisms such as social risk pooling. Individuals tend to have great difficulty hedging longevity risk, which includes the risk of outliving their retirement resources and catastrophic health shocks. Relying solely on individual efforts to finance old-age consumption may thus accentuate income and wealth inequalities in society.

To this end, the Central Provident Fund Lifelong Income for the Elderly (CPF LIFE) scheme provides coverage for the retirement income needs of Singaporeans. It is financed through compulsory monthly contributions to one’s CPF account and provides a monthly payout during old age for as long as the policy-holder lives.

Another scheme, MediShield Life, provides life-long coverage for Singaporeans’ hospitalization expenses. It is a basic health insurance plan, funded through mandatory yearly premiums, which helps pay for large hospital bills and selected costly outpatient treatments, such as dialysis and chemotherapy.

Japan: Long-Term Care Insurance and industry innovation

Japan is another rapidly ageing Asian country. Currently, about 25% of Japan’s population is above 65 and this will increase to 40% by 2060. Such a demographic shift would severely strain Japan’s established pension system and Japan’s ageing workforce has already started to slow down the Japanese economy.

The Japanese government has taken a multi-prong approach to meet the needs of the Japanese population and boost economic growth. In 2000, Japan implemented a comprehensive Long-Term Care Insurance, known as one of the most generous and comprehensive health insurance in the world. The insurance pays for professionally designed and government-approved care plans that offer the elderly a choice of different care models, such as living in assisted-care facilities, home care and assistance with grocery shopping. The Japanese government has continued to improve care plans in 2011 by introducing more care models that integrate healthcare, preventive care and long-term care.

On the economic front, the Japanese government has also spurred the creation of the MedTech and aged-care industries by tapping into Japan’s historical advantage in industrial manufacturing, design and customer service. For example, helped by state funding, Japanese firms are now investing in the design of care robots such as Paro the robotic seal, mechanical care aids for caregivers and innovative regenerative and cell therapies. Not only will these emerging technologies produce products and services that will meet the needs of Japan’s ageing population and lower the cost of care, but the government’s investment could also create a new growth industry for Japan.

Taking a whole-of-government and long-term perspective

Singapore and Japan are doing the right thing by looking long-term and starting early. As the examples above show, what both countries also have in common is tackling the issue holistically from different angles. Ensuring that the future elderly population has sufficient health insurance cover serves to protect the country from an excessive healthcare burden as the population ages. Both countries are also thinking ahead about the jobs and character of the economy as the population ages. Longevity will affect every aspect of a nation. Countries need to take a whole-of-government approach to make sure they are sufficiently prepared to reap a longevity dividend.

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with our Terms of Use.