Is blue light being "demonized"?

on

As day turns to night, twilight casts dim, cool tones. This transition signals to humans that it’s time to sleep, but some studies suggest that people are interrupting this process with one persistent habit: looking at their screens.

Concerns over the way light can disrupt sleep and the body clock’s ability to maintain healthy sleep rhythms are “certainly justified”, Timothy Brown, study co-author and researcher at the University of Manchester, tells Inverse.

Body clocks

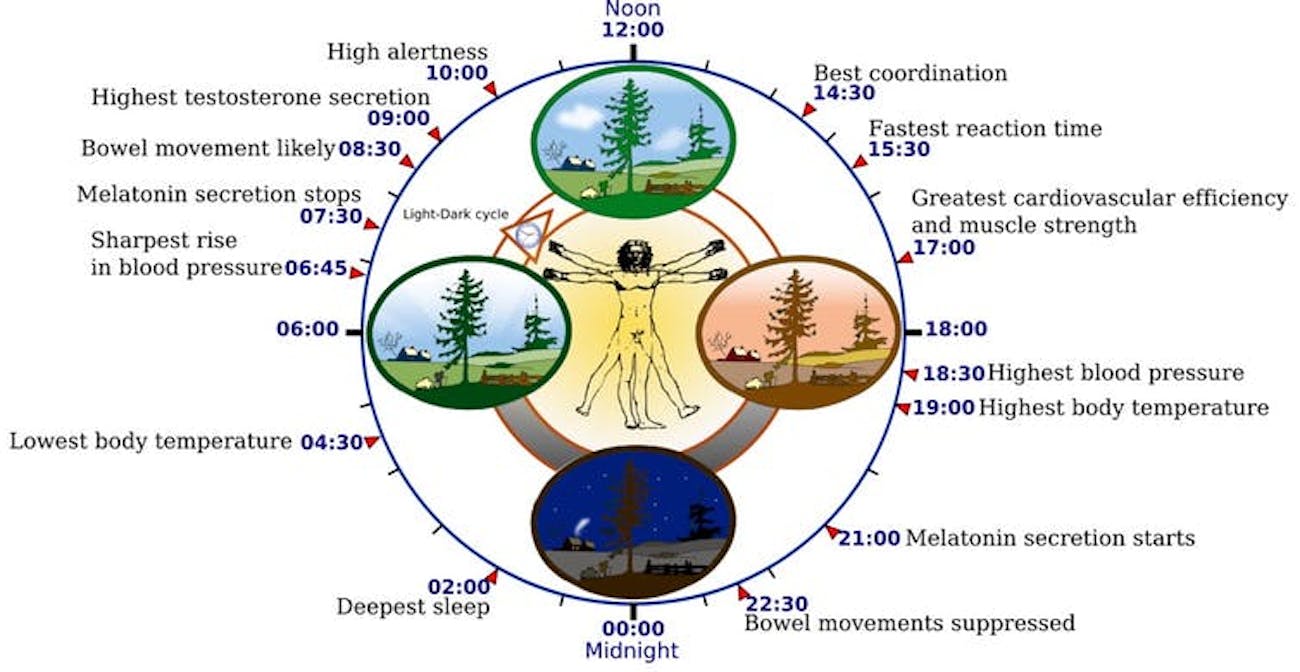

To understand blue light’s effect on sleep, we have to start with the circadian rhythm or body clock — the process that regulates hormones, digestion, and temperature. Most people’s circadian rhythm is about 24 hours.

Sunrise and sunset naturally regulate humans’ sleep patterns, with light exposure determining how tired or alert people feel. Light is filtered through photoreceptors in the eye, including a specialized protein called melanopsin. When we wake up, melanopsin measures the brightness of daytime light and halts production of the sleep-inducing hormone melatonin.

Throughout the day, bright light keeps us awake, boosting attention and mood. As light dims in the evening, melanopsin triggers melatonin production, making us drowsy and helping us fall asleep.

Blue light has shorter wavelengths and is more energetic than white and yellow light, and melanopsin is better at detecting shorter wavelength photons than longer ones. In turn, past research indicated that blue light is more disruptive to our circadian rhythms than other light. It’s that conclusion that’s being challenged in this new paper.

Blue over blue

Phillip Yuhas, a researcher and optometrist at Ohio State University who was not involved with this new study, tells Inverse that there is good evidence that short-wavelength, blue light is the most effective color at dampening the production of melatonin.

“Electronic devices emit more blue light than other colors,” Yuhas says. “So exposure to blue-light-heavy devices before sleep does seem to have negative consequences in living, breathing human beings.”

But the hype over potential harm from blue light may be unwarranted.

“The claims that the blue light emitted from electronic devices can damage the retina are almost certainly overblown,” Yuhas explains. “I also think blue light is demonized for being the sole contributor to the effects that electronic devices may have on sleep.”

Meanwhile, Brown’s new research challenges the dominant view that blue light is all bad, and indicates that it may actually help body clocks stay on track. The study, which explored the influence of color on circadian rhythms, suggests the whole sleep disruption situation is far more complicated than blue light is bad and white or yellow light is good.

Brown and his colleagues used specially designed lighting that allowed the team to adjust color without changing brightness. Subsequently, they exposed mice to varying colors of light at different intensities. Although mammals perceive color through retinal cone cells, exactly how this cone-rod system interacts with melanopsin isn’t clear.

In turn, they discovered that while all lights are stimulating, in this case, blue light can actually be less stimulating than yellow light. This finding suggests yellow rather than blue colors have the strongest effect on the mammalian circadian system. Dim, blue light may actually be more conducive for sleep than warmer, yellow light because it better mimics natural, twilight tones seen in the evening.

Twilight is both dimmer and bluer than daylight and the body clock uses both of those features to determine the appropriate times to be asleep and awake. Even though the short wavelengths of blue light are known to disrupt melatonin production, the blue color may buffer this effect.

Better sleep

This study adds to the blue light debate, and more research in humans is needed to figure out how color and wavelength of light impact circadian rhythms. But if the study’s findings are replicated in humans, they could lead to new approaches to lighting spaces in the evening and recommendations for device use.

There are some practical takeaways for the present as well. The study suggests that it’s likely less helpful to wear blue-light glasses at night, instead of just turning down your home’s overhead lights.

Meanwhile, shifting your phone into night mode — changing the light from blue to warmer— could be doing more harm than good. This study argues that apps like f.lux and Apple’s night shift mode send the body mixed messages. That’s because the tonal shift they create resembles daylight tones, rather than twilight tones. Instead, try adjusting your screen brightness to the dimmest setting.

Regardless of color, light exposure in the evening is keeping us up at night. To be on track to get the amount of light you need to be both happy and well-rested, Brown advises maximizing exposure to white light and sunlight during the day and minimizing light exposure in the evening.

Meanwhile, Yuhas makes the case that all bedrooms should be “device-free” if people want to get a good night’s sleep.

Abstract:

In humans, short-wavelength light evokes larger circadian responses than longer wavelengths [1, 2, 3]. This reflects the fact that melanopsin, a key contributor to circadian assessments of light intensity, most efficiently captures photons around 480 nm [4, 5, 6, 7, 8] and gives rise to the popular view that “blue” light exerts the strongest effects on the clock. However, in the natural world, there is often no direct correlation between perceived color (as reported by the cone-based visual system) and melanopsin excitation. Accordingly, although the mammalian clock does receive cone-based chromatic signals [9], the influence of color on circadian responses to light remains unclear. Here, we define the nature and functional significance of chromatic influences on the mouse circadian system. Using polychromatic lighting and mice with altered cone spectral sensitivity (Opn1mwR), we generate conditions that differ in color (i.e., ratio of L- to S-cone opsin activation) while providing identical melanopsin and rod activation. When biased toward S-opsin activation (appearing “blue”), these stimuli reliably produce weaker circadian behavioral responses than those favoring L-opsin (“yellow”). This influence of color (which is absent in animals lacking cone phototransduction; Cnga3−/−) aligns with natural changes in spectral composition over twilight, where decreasing solar angle is accompanied by a strong blue shift [9, 10, 11]. Accordingly, we find that naturalistic color changes support circadian alignment when environmental conditions render diurnal variations in light intensity weak/ambiguous sources of timing information. Our data thus establish how color contributes to circadian entrainment in mammals and provide important new insight to inform the design of lighting environments that benefit health.